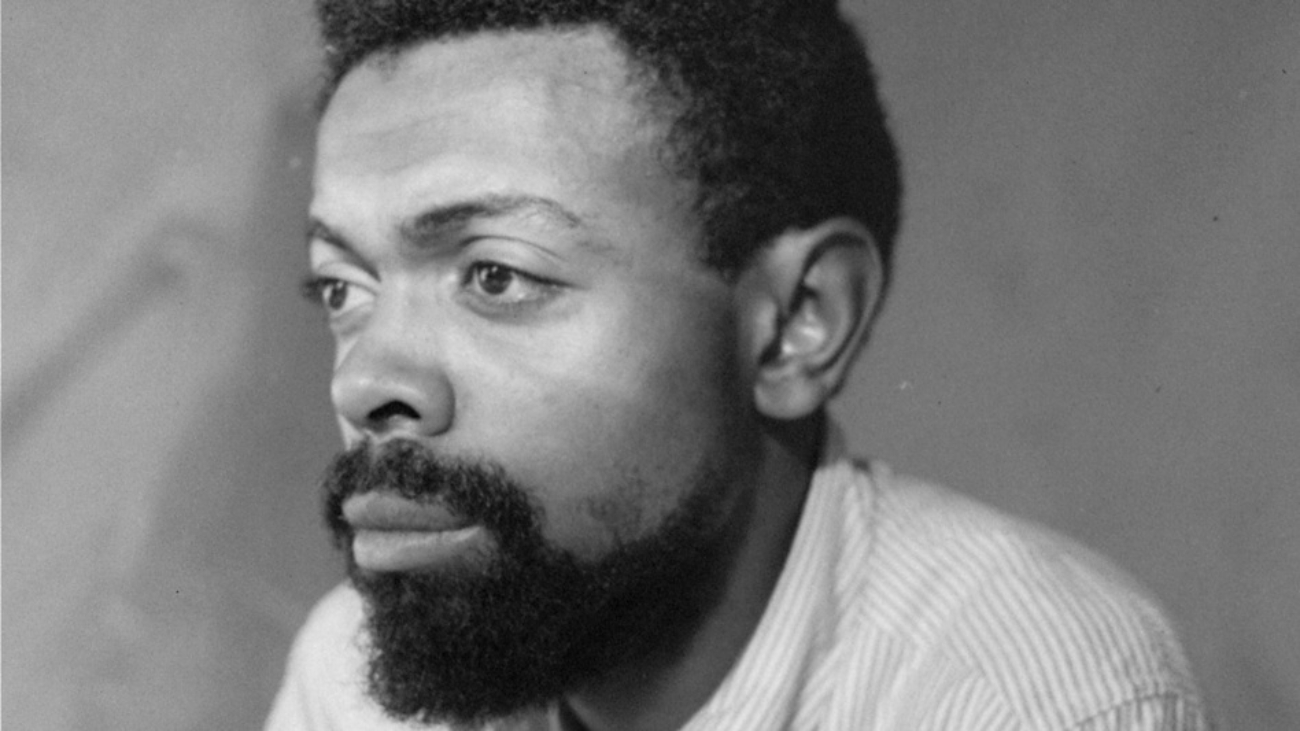

Decide for Yourself

Pulse: I’d like to talk to you about the relationship between truth and creativity. How important do you think truth is to the experience of writing?

Amiri Baraka: If you don’t think about what’s true when you’re writing, then it’s just some kind of propaganda. If you’re not trying to find the truth, and if you’re not at the same time communicating that truth, then you’re actually a very negative force. There’s nothing more dangerous, according to Mao, than a skilled artist who represents bad things. Skilled artists who represent evil are the most dangerous forces in the world because they can make you believe it. We’re constantly perceiving things, like we have antenna, we’re always learning, but the big question is: how are we going to use it?

You talk about process and movement a lot in your writing and I’m interested in how those things relate to truth. Because it seems you’ve been through many different stages, often going from one extreme to the other. Has the truth been different for you at different times?

Yes. In the same way that what you know when you are 9, you might reverse when you are 12.

But your changes have been quite radical. You’ve shocked people. You’ve been inconsistent.

And I don’t see anything wrong with that. I think people should understand that if you think the same things when you’re 60 that you thought when you were 30 then something must be wrong with you. What have you been learning? What have you been waking up to? It’s not about always being right. You’ve got to be strong enough to be critical of yourself and then move on. To say this is why I thought this and this is why I don’t think it now. Self-criticism is a good thing. It’s like going to the bathroom: if you don’t go, then you’re going to be full of shit. You have to get rid of the waste material and that’s a process that goes on all the time. That doesn’t mean it’s easy: sometimes it’s very hard to get rid of things, even when you know they’re negative.

Because of fear?

Fear is a big part of it. People are afraid of losing what they have. It’s also hard to say what you think when you know it’s going to be opposed, or when you think people are going to jump on you for what you’re feeling.

So why go through all this effort in the first place? Why is saying what you feel worth taking risks and making mistakes?

Because you want to have a healthy mind, a healthy spirit. Because you know your mistakes might make something clear. As much as people might jump on you or taunt you, they can’t really hurt you if you’re clear with yourself, if you know you did something because you believed in it; whether it’s taken as wrong or right, it’s what you had to say. That kind of strength is the thing you should never deprive yourself of. People become cowed by society, prostituted by society, suicided by society. I read an article once where Van Gogh was described as “the man suicided by society’. People couldn’t handle the way he saw things. A lot of stuff happens and we just don’t want to handle it.

But isn’t what you’re describing more on the side of life than death? Isn’t it about dealing with truth as something alive and dynamic rather than static or fixed?

Yes. But a lot of people aren’t conscious enough to go that far, they aren’t aware at all. They lack true self-consciousness, and they aren’t even looking for it. To be aware of who you are essentially, to be aware of where you come from and of what you want, that’s a strong quality and it has to be sought; you have to work for it.

But are people who aren’t consciously dealing with their truth living worse lives than those who are? Are they unhappy?

It’s not always a matter of happiness.

But is there a reason to be more aware? Do you think this is something we should feel responsible for or try and change?

Of course it’s something we should want to change. If people weren’t so unconscious they wouldn’t allow themselves to be abused. The more conscious a society is then the more that society will develop. Everybody’s got to know enough to walk down the street without falling down. To live in a world where the ignorant outnumber those who are aware is a very dangerous thing. Whether the ignorant mean you harm or not, it’s still dangerous. They can’t protect themselves or anyone around them. Just like the current ignorance with global warming. By the time everyone becomes aware of what’s really happening,we might already be floating down the river.

We might. But its funny how quickly the awareness of something can spread once it begins. It’s like dominoes falling.

That’s why you learn so much during periods of revolution. When there’s revolutionary turmoil, people learn in two or three days what it would otherwise take them years to learn. They’re shocked into awareness because things are so immediate and society is turning over so rapidly. People aren’t generally encouraged to think. They’re encouraged to eat and copulate and work. They aren’t encouraged to do research and learn. Mao said ‘be good at learning’. Take the time to understand that you don’t understand. There are a lot of things you don’t understand. They are a lot of things you might never understand. But you should always be trying. You’ve always got to try and find out what’s out there because you have to know what the other paths are before you can reject them. You have to learn, and then you have to clear away what you’ve learned and find your own answers.

I learned your poems in school before I knew anything of your autobiography. I identified with your poems as they related to my own life, not understanding the context from which they came. Do you think it’s strange that a young, white girl would connect with a poem like Return of the Native, a poem you wrote in a time when you were considered a Black Nationalist?

It’s not a question of who wrote it or when; it’s a question of sensibility. It’s a question of what’s immediate, not what’s on all the sides of that. If you can sense what’s human in it, then you’re at its essence.

There’s a Guatemalan poet named Otto Rene Castillo who writes “If you can feel the man beneath these words; if you can feel the human being beneath these words; if you feel real life beyond what I am describing, then we are brothers and sisters” and that’s what art is supposed to do. Even if you think you hate people, you still want them to understand what you’re saying; you want them to get the emotion, the feeling. You communicate with people at all kinds of levels. It’s about human beings. They come from diverse places, sizes, shapes, colors, wants, needs, but there’s always a need for recognition. Recognition is what helps us understand each other. The question now is: when will we advance enough to create societies based on our ultimate humanity rather than all the other bullshit that separates us and makes us enemies?

Do you think we can do that?

I think we’ll either do that or we’ll perish. We’ll either find the way or we’ll disappear. It’s another epic: either we perfect this society in a way that allows us to live together or we’re all dead. Global warming makes it obvious that it’s not in any one person’s hands. We’re part of nature, and we have to be in tune with it, with the body of it, or it will get rid of us. There are levels of agreement that we must ultimately come together and see. At a certain point it’s just abstract to think about individualism. Individualism is an abstraction in the face of this. The same thing goes for social relations, for international relations: keep fooling around in Iraq and it’s going to be the same thing. Are we going to keep putting

the whole world in jeopardy so a little group of us can steal? That’s insanity.

Do you think that kind of understanding starts on a smaller scale? With our friends and lovers? You and your wife Amina have been married for over 40 years now. I imagine that has also required a similar process of learning.

People ask me how me how we’ve stayed married so long and I say ‘Because we want to be married’. It’s a question of need, what does another person have that you need. A relationship is also about finding yourself there, because if you don’t find yourself there then you’ll leave. Marriage is a completion, this half and that half, and it’s the real stuff, not the bullshit. The life of a single individual is limited no matter how smart or how brilliant or how rich you are. Human beings are social animals. There’s no such thing as a society of one. Sometimes people think they’ve got to create the ideal world when really what they’ve got to do first is just learn to live with another person.

So it’s about being open or true, even if just with only one person, letting them see you as the monster or the angel or the good guy or the bad guy or whatever?

Yeah.

Do you think people are able to consistently let go and feel that?

Well people aren’t taught to be like that, to express themselves like that, or to be that comfortable with their own truth. Being open is very difficult. Saying ‘I need you’ or ‘I love you’ and really feeling it is very difficult, much more difficult than just using the words. Anyone can use the words because they’ve heard them said in the movies; they’re just going through the motions. To actually express that at the utmost level of sincerity is a hard thing because none of us wants to be that naked.

Do you think that same idea is related to being creative? Getting to that same place?

I think ultimately that’s the only place you can go to or feel when you’re creating something. I don’t know what you’re being creative about, unless it’s about going there.

interview at Amiri and Amina Baraka’s home,

Newark, New Jersey, 2007