Interview by Andrea Hiott, 2006.

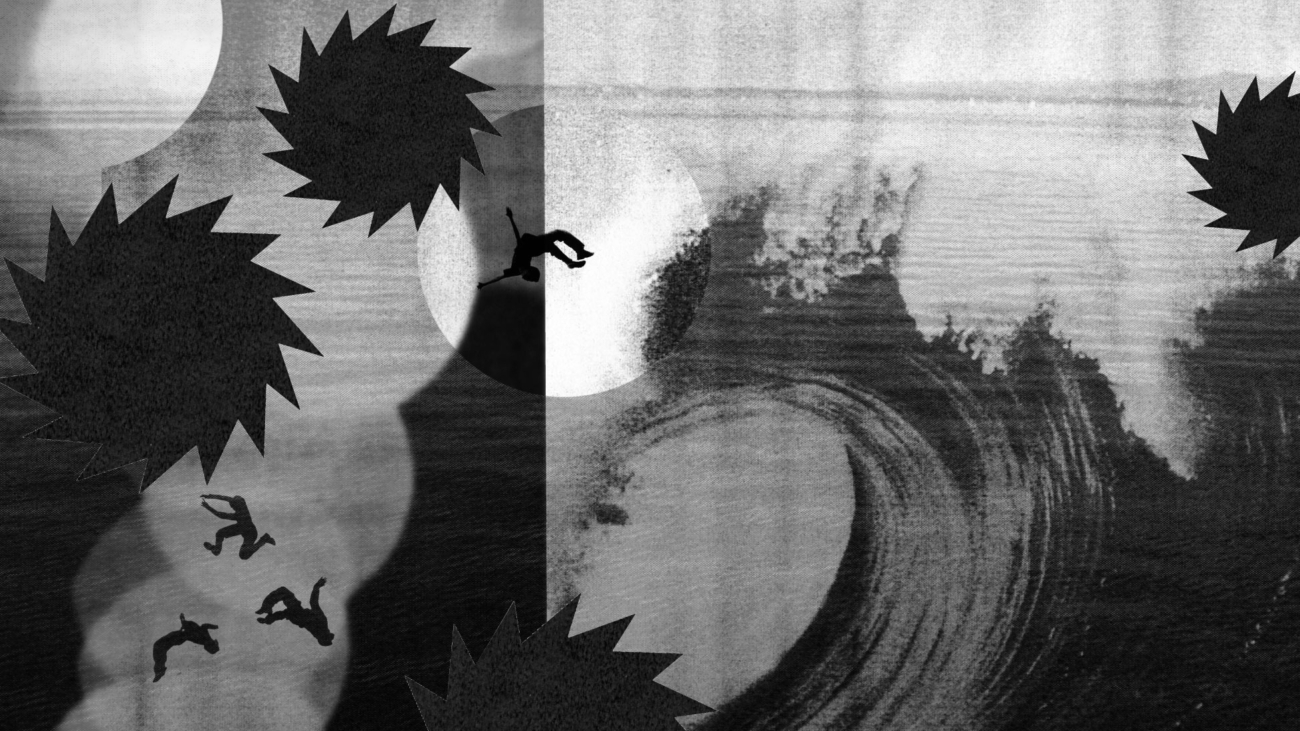

Artwork by Ann van Poperingen.

A Discussion of Love and Poetry with Renowned Rumi Translator Coleman Barks

Sufi mystic and poet Jalaluddin Rumi was born in a small town in present-day Afghanistan on September 30th, 1207. His poetry is the poetry of love – erotic love, divine love, the love of friendship, an annihilating love. His words are an ocean, always rhythmic, always changing. Relationship consumes him. When speaking about his meeting with Shams – the most pivotal friendship of his life – Rumi says, “I was raw, then I got cooked, now I am burned.” It is a fire of the heart, and comes from a burn that is endless.

Coleman Barks first began translating Rumi’s poetry in 1976 after his friend, the poet Robert Bly, handed him a stack of scholarly translations by a Cambridge Islamisist and told him: “These poems need to be released from their cages.” Barks’ work is a matter of transforming Rumi’s poems into free verse, rewriting them in the tradition of Walt Whitman or William Carlos Williams, in American English. Because of Coleman Barks’ translations, Rumi is now the most popular poet in the United States.

PULSE: By the tone of your translations, it’s easy to imagine that you enjoyed delving into them as you worked. It also seems that that this type of translation is intuitive rather than something studied or learned. Is that true?

COLEMAN: Yeah, I suppose. When I first began to do this in the fall of 1976, I would walk downtown after teaching classes, mostly classes in Modern American Poetry, and sit at a café and begin working on these poems. Perhaps because it was so different from what I’d been doing all day, it felt more like a release than like work to me, a release into a space of freedom. I loved being there in the space that these poems inhabit. I’ve never taught Rumi and I never want to. I never want to explain what these poems are about, because they are something to be experienced, like a friendship, or silence, or love.

That echoes what he writes about for me.

Yes. It does. He’s always trying to put you in that shared place of inwardness, into whatever the heart is – the Qutb as the Sufis call it – into that mysterious place that his poems come from and live through.

That place of connection or silence or feeling almost appears impossible to describe linguistically. Perhaps it can only be triggered, suggested?

Well you can’t really put any experience into exact words. R-o-s-e is not what we use it to signify. There’s always an awkwardness to language when trying to approximate the living world. It’s impossible. And on top of that, there’s the impossibility of bringing medieval works of an enlightened master through my mind and into American English. It’s absurd but some things are going to be done regardless of their impossibility.

It’s not easy to talk about what makes a good translation. Or why one person would prefer one poet’s style or work to another’s. It comes down to connection, but that’s a vague linguistic concept as well.

Well, there’s something to be transmitted in a poem, and if that is transmitted, then the poem is working: it’s a transmitter from presence to presence. Rumi says that you must listen for presences inside poems. You must let the poems take you where they will, follow their private hints and never leave the premises.

What do you think that is, ‘the presence’?

Well it’s both individual and cosmic. It’s the mystery I think of – of –

– of why two people connect – of why anything connects?

Right. And nobody knows why. The Sufis say it is God’s sweetest secret – how someone gets attracted to someone else, how two presences coincide with each other and mix.

Maybe we don’t want to know the answer.

Yeah (laughing), it just gets partially said in all our love songs and all our poems and plays. And so that’s what is ultimately so illusive and frustrating and glorious about the whole fact of loving.

It’s an interaction, so I guess there are never two static parts that can be defined.

It’s a living thing, yes. But you can find images that do some of the work for you. Images let you feel what it’s like inside. They carry the information and the feeling and the tone.

Of course different images are suggested depending on the reader.

Frost’s poem for instance: Stopping By the Woods on a Snowy Evening. You stop by different woods than I do.

And it’s a different time of evening. But getting back to Rumi, something about his poetry that I especially connect with is its constant hint of movement. He seems to speak of a universal movement, something that it is a part of everyone and everything. Do you feel that conveyed in his writing?

He seems to think everything is moving, yes. The metaphor he uses a lot is an ocean that has no shore: it’s always in motion and always separating itself out from itself in the way that water evaporates and rain comes and that same drop of water is then a part of the ocean again. That process of continual changing and exchange is a celebration in Rumi. It’s what the poems embody, particularly the long poem that he wrote over the last 12 years of his life. That poem is an oceanic field of stories and jokes and all sorts of interruptions. It deals with so many things simultaneously that the fluid structure of it seems to rather gradually and chaotically become an image for what the soul is outside of time. The poem must be read linearly but you feel a kind of synchronicity happening, a simultaneity that is happening inside the poem itself. Is this making any sense?

It sounds like you’re trying to describe life.

Well, it’s just as chaotic as consciousness. So, it’s a form, or a model, for the psyche – not as an individual thing but as a field, or as interweaving fields, of stories and voices. It’s like a crowd, a community of soul growth happening before your eyes. Actually, I don’t think we’re even capable of understanding such an artwork fully at the moment.

Maybe not, but the more we come to know of our own lives, the more we might be able to understand what he was conveying with his. When Rumi speaks about “the ecstasy” or “burning the forms,” do you think he’s speaking about the experience of feeling one’s connection or absorption in this movement, with feeling that one is a drop in the ocean or the ocean itself or…?

The feeling of intensity that he calls burning or longing – well, this is a strange thing to try to phrase but – he says it is somehow the same as what it is longing for: the intensity is part of its same mystery, that ocean of being. The longing is what the longing is longing for. As a grammar, it almost disintegrates.

Well this is what confuses me, because it seems that we constantly want this melting or longing or ecstasy and yet we are always inside of it.

Well we have the sense of being separated, so we have grief and we have fullness and they’re all part of the same package of deep being. They aren’t necessarily to be ranked. For the Sufis, separation and bewilderment are just as good as union. Everything is God for them. They say that there is no reality but God; there is only God. So whatever is passing through you is the motion, the divine. All motion is from the mover, they say.

So it’s passing through you but it’s also you.

The image he has is the guesthouse. All these emotions – even ecstatic love – pass through you. So you are the host, but you are also the emptiness. There’s something here that connects with Buddhism – there is an emptiness and a vast space that is inhabited by emotions as they come through. Sometimes they are burning and sometimes they are cold. Sometimes they are thoughtful. Sometimes those emotions are intensely rational, and sometimes they’re just gibberish.

So can love be seen as a goal?

It seems that it’s sort of built into the initial impulse, so that the question and the answer are the same thing. It’s in every exchange.

Would you say that love is the main theme of Rumi’s work?

I would. Love as the dissolving of the personal into the Divine. The image takes many forms. It’s the net inside the windstorm. There’s a little bit of the ocean inside the fish, which is what takes him to the ocean. It’s all just different forms that the movement takes, the attraction. It takes one out towards the center – out of oneself and into the center of oneself. The more you talk about this the more it turns to dust in your mouth.

But I love that impossibility – movement being obscurely reflected by its inability to be reflected. Or whatever. Yeah, it does turn to dust.

But Rumi says that same thing in every other sentence. He says: This is not saying it: this cannot be said.