One Man Orchestra

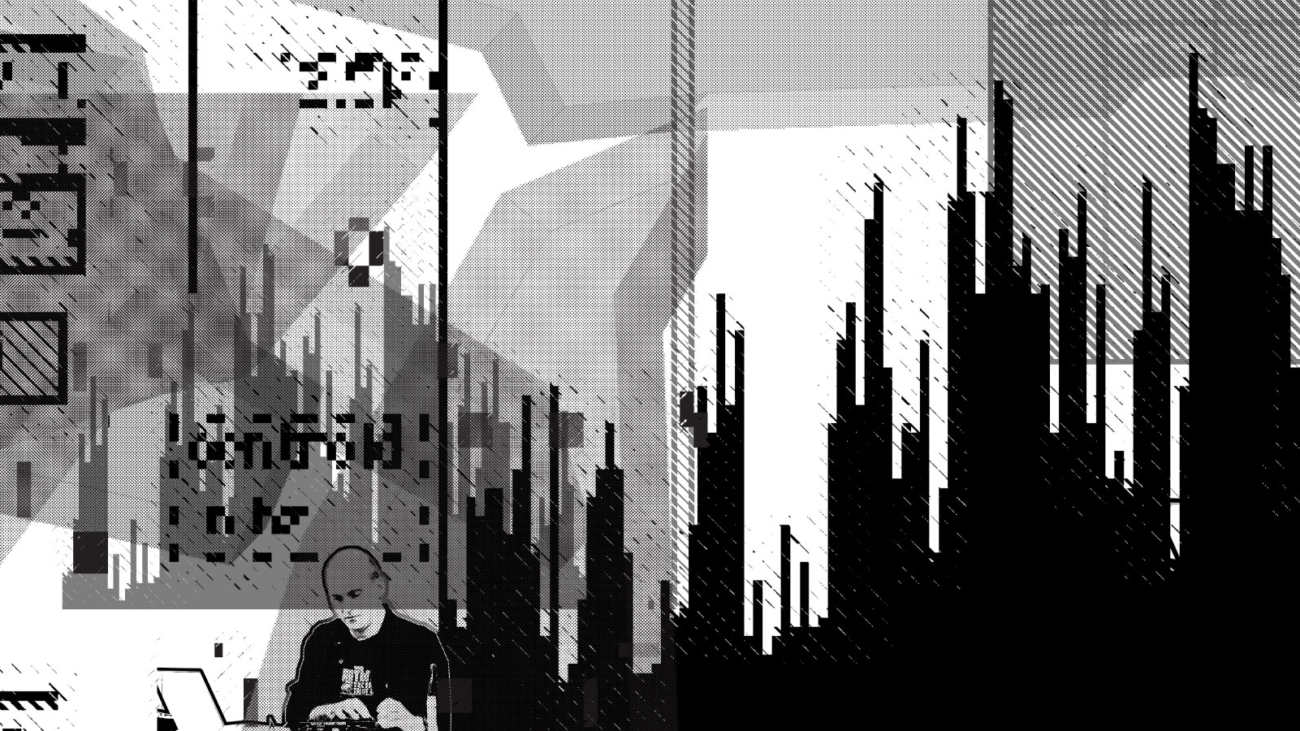

The club is full. All eyes in the room are focused on the man on stage. The man’s eyes are fixed on the screen of a laptop. He makes subtle movements with his fingertips as he stares at the machine, his face bathed in a pale light. Perhaps reminiscent of a science fiction book from the 1950s – these events happen every night in cities all across the world. The laptop musician is a new breed of artist stemming from various origins – the academic electronic music world, the dance club DJ scenes and, some would say, the improvisation of jazz music as well. Even though the glowing Apple adorns the stages of mainstream performers like Radiohead and Bjork, many critics and listeners still insist that there are problems with the way this new variety of musician relates to the conventions of live performance. Audiences ask: “What are these sounds? Where are they coming from? And what are we watching?” As a member of this new musical community, I wanted to address some of these questions. And who better to ask than one of the original laptop musicians, Kim Cascone? Not only is Cascone an influential musician, he’s also the founder of the well-known electronic music label Silent Records and has collaborated with a number of renowned artists in various disciplines, such as Japanese noise collective Merzbow, filmmaker David Lynch, sound artist Keith Rowe, and new wave legend Thomas Dolby. I met with Kim in Berlin to ask him about some of the questions people have when it comes to making music with a computer. To start off, I had him compare his instrument, a laptop with self-programmed, music-making programs called “patches”, with a traditional acoustic instrument.

CASCONE: Well it’s kind of like comparing a spacecraft with a go-cart. With traditional instruments you’re hardwired into a familiar sound vocabulary; there’s a certain expectation that happens. If it’s a saxophone, then it reinforces that sound – that‘swhat a saxophonist does, that‘s what it sounds like – so you expect all the notes to sound a certain way. But with a laptop it’s really open, it sounds like whatever you focus on. For instance I could construct a patch recreating all the sounds happening in this room right now just by recording them and layering them.

DOUGHERTY: But if there is no common voice, what prevents artists and audiences from being overwhelmed by so many sounds and possibilities?

Well there are still signature sounds that people naturally walkinto. For a while there were the ‘clicks and cuts’ – using glitch as a rhythmic marker – then there were also the styles that were more collage or guitar-oriented. Now the Internet and new ways of sharing music has created a deluge of material. You have to sort through terabytes of music until you get to a piece that might be good. I don‘t think we’re seeing the true potential of the laptop being used right now, but there are a few artists who are paving a new way through all this material, people who are trying to invent new languages.

To go further into this language idea – in some genres, acoustic jazz for example, there is a set reference. People either go against that set language or they add to it, but its always there. Does computer music have a referential language?

I think every genre of music has its base sounds. In computer music, there are the sounds of the artists who were pioneers, the sounds of Jean-Claude Risset or Matthews for instance. They all had their algorithms. Whether it was with additive synthesis or linear predictive coding or with FM, all these technologies have developed a dictionary of words and phrases that people have latched onto.

How about the visual aspect of this music? Do you think that’s one of the major differences between laptop performance and acoustic performances?

There’s a lot of history that goes into performance as an art form. The original songwriters were like troubadours and minstrels that roamed the countryside. They not only sang songs but learned songs from other regions. They transcribed and customized them into their own language and their own aesthetic – that‘s how music traveled. And it was still entertaining. Then later opera came along and really spectacularised the idea of performance. Much later, with electro-acoustic music, or what was then called acousmatic, the music became the performance rather than having a performance to a piece of music. There was a shift from the foreground to the background. And I think that shift is what laptop music suffers from – if you want to use the word suffer – because it isn’t about someone getting up there and playing a guitar with their teeth or setting it on fire or any of those sorts of spectacular signs or signifi ers that we’re used to in pop culture. It’s more about the music and the idea of the composer. People have a hard time weaning themselves off of the spectacular portion of performance. That‘s why I think more people find laptop music to be boring or more difficult to relate to than other kinds.

I read an interview where you talked about the gestural theater, the notion that music performance needs to carry a visual counterpart. Do you view visuals as a negative aspect of a performance?

No, not at all: it‘s purely valid. I don‘t have any problem with going and seeing a performer and there being some kind of gestural theatre. I don‘t dismiss it. I don‘t fi lter it. I enjoy it for what it is, but the laptop’s a different thing. You cant expect the same kind of gestural theatre from an instrument that is mostly software based. Computer music relies on micro-movements to change states rather than relying on grand gestures. When someone is playing the saxophone, he or she obviously emotes and presses keys and there’s a certain pressure in the jaw and so on. All that goes into the theatre of the performance in acoustic music, but you don’t have that interaction when you’re using a computer.

I know you often use background visuals as a part of your performance. Is that a substitute for the visual theatre of an acoustic instrument?

It’s hard. I often feel like I’m cheating because I’m trying to replace a type of traditional theatre for people. I sort of transfer it behind me, putting images on the wall or whatever, rather than just saying “Look this is what the music is about”. It’s really about me controlling a bit of software, developing music in real time. It’s about a laptop, not a saxophone or a guitar. That‘s my instrument and that‘s how I perform.

Kim Cascone studied electronic music at Berklee College of Music, Boston and worked since the late 70‘s in electronics. In the late 80‘s Cascone was assistant music editor for David Lynch‘s films ‚Twin Peaks‘ and ‚Wild At Heart‘. In 1986 Cascone founded the record label Silent Records, where he released first results of his project PGR. In 1995 he started work on a triology called Blue Cube. Cascone now releases music on Sub Rosa, Mille Plateaux and runs a small vanity label called Anechoic.