Roberto Ferri first came to NYC to attend film school. He was born in Italy, and by the time he moved to NYC he already had a degree a degree in film from the National Film School. Robi first started making films when he was only 14 years old. Those first films, and the films he made while in school, were more traditional narratives. In NYC, however, the narratives turned into The Still Cycle, a group of videos where the center of the action is a person who, in the midst of the normal movement and chaos of a day, remains still. The contrast is more shocking than it sounds: this still presence at the center suddenly causes one to see normal activity and movement in a very new way.

The first “Still video” that Robi made came as surprise even to him. It lasted as long as a typical workday, a video of a young man standing completely still in front of a camera in his room. It was a spontaneous gesture that came one morning after his father called from Italy to tell Robi it was time “to get busy, to make something of himself, to do some real work”. When he hung up the phone, Roberto’s immediate reaction was to turn on his camera and for the next eight hours, to only stand still. From there, the cycle has expanded into the streets and cultural institutions of New York City and other cities around the world. Roberto and I met in the West Village one winter day to discuss how he came to making such videos, and what The Still Cycle really means to him.

Pulse: What kind of movies are you generally drawn to watch?

Roberto Ferri: I’ve always liked to watch movies that reflected the pace of real life, that had a similar timing to the way we experience the world. I’ve been watching a lot of Andrei Tarkovsky lately, and I think he’s someone who often does this. There’s also the work of people like Bill Viola or Bruce Neumann, where the medium of film is as much about timing and an element of silence than it is about story or plot. I’m interested in films that do not try to escape the loneliness, silence, and melancholy that I experience in real life.

It sounds like you’re interested in the space between things. Which, in a way, is the same thing as being interested in the space that holds things, in the background, in the canvas, in the pause.

Yes, exactly. I’m interested in the paradox of the silence that is necessary for the noise. I’m interested in the way the pause is mixed up with the activity. I think that interest stems from my childhood. I grew up in a very middle class household where a lot of emphasis was put on activity. My parents thought it was very important to always be active, to be a good student, to wake up early, to always do your homework, to be sure and have lots of friends, to have a steady girlfriend. And yet, in a lot of ways, I was naturally inclined to the opposite of all of that. I spent a lot of time alone, watching movies and reading and my parents were confused by this, always wondering why I was “wasting so much time” with all these boring movies when I was just a kid. They didn’t think it was healthy. They wanted me to be like someone in an American movie – always active and moving and go, go, go. So basically I eventually gave in to their pleas and I tried to do this, I went against myself to try and live this way and keep busy. I pushed myself because I thought it was the right thing to do because my family was so concerned about this. I was a good son. I went out a lot. I was a good student. I didn’t make a lot of trouble for my family. But there wasn’t something about me that was lost in all that. So I think that’s an important point for my work now. I think that’s how I got pushed to that moment where I woke up and decided that all I was going to do was stand sill.

Did you feel like you were breaking away from your old life by doing that?

I felt like I was stopping time for a bit. If you imagine your life as a timeline, you are born and you die and you should fill all this space between with as many things as possible. You’re not able to think about consequences at first. You are too young. You just follow it. You just try and fill it up. You stuff your time as full as you can. At least that’s what I did. There was always something before and after school to do. There was soccer practice. There was getting a job. There was university. And on and on. It never finishes. There’s no end to this. And day by day, you lose yourself.

Do you mean that by stuffing our days so much we lose an awareness of who we really are?

You don’t let yourself be there long enough to be aware. You feel like something is wrong because you haven’t given any thought or space to whatever is really you, is really real, but you think it’s crazy to feel that way and you keep doing things to fill your time, as if that will be the thing that defines you. But the more you don’t follow yourself and the more you follow something else instead, the more insecure you feel and the more guilt you feel and the more you feel like you have to do even more to make up for that. So it’s this big circle and you get really confused in that. You never just step back to see how you really want to live your life. You just pack the timeline full of things. I was doing this, but day by day I realized that this timeline doesn’t even belong to me. None of that stuff on there was even mine. And I didn’t know what I was.

And it took that extreme action of just standing still for eight hours to break through and realize all of that?

I’m a kind of masochist. I like to go to the place that I hate the most or that is the hardest for me because that’s where I can see new things. I have to confront all this in myself in those places. I have to make something out of it, be creative. I came to NYC with this hope that maybe I could solve myself here, but I was even more stressed when I got here and realized it wasn’t any better; in fact, it was worse. I wasn’t able to do anything. I just stayed in my room without windows, reading. I hardly even went to school. I realized I was just filling my time with sadness again. I was still following the timeline and I didn’t know how to step away. So that morning when I was really sad in my room all alone and my father called me and said “What are you doing with your life?” – I couldn’t lie to him. I told him I was sad and that I had no idea what to do. And he had his usual response which was to say things like “I told you not to go to NYC. You’re always wasting time.” After that phone call the pain was so extreme that I just turned on the camera and stood there without moving again for the next eight hours. I don’t know where that came form but I just suddenly had to do it. I just had to have that response. And I did it every day for one week. Like a job. Every day I woke up at 8 o’clock and I prepared the camera and I stood still for eight hours.

It’s like you pushed yourself over the edge.

Yes. I needed to do this. It was necessary. I don’t know how to explain it. But it was so unnatural for my body, it actually really hurt my body. For three or four hours it would be quite painful but there was something in that too, in forcing myself to bear it and stand still through it. It was a serious process. I wanted it. I felt it was really good for me to do this. To stay still. To just wait. To just be there. To see what happened.

What has changed from doing this?

Well, it changed everything and nothing. It’s this same paradox I was talking about earlier. After I did this, it was a whole new world and it was the same world. I’m not the same person as before I did this, and I am. It’s like if you imagine that timeline again, the stillness was like getting back to the zero point, the point where there is no activity, no movement. I just got back to the space, the pause, everything that is not the activity. None of the things that stress me were in that space. I can still go to that place, and all the stress is gone there… So I don’t know what that really solves but I know it is a good thing, a healing thing, to reach this zero point, this place that is still. This is something good for me. Even if I can’t say exactly why.

But isn’t that space you’re talking about always there?

Yes. It’s always there. At any moment.

Does the stillness, or even just knowing the stillness is there, change the way you feel when you aren’t being still, when you’re back in the timeline, when you’re active?

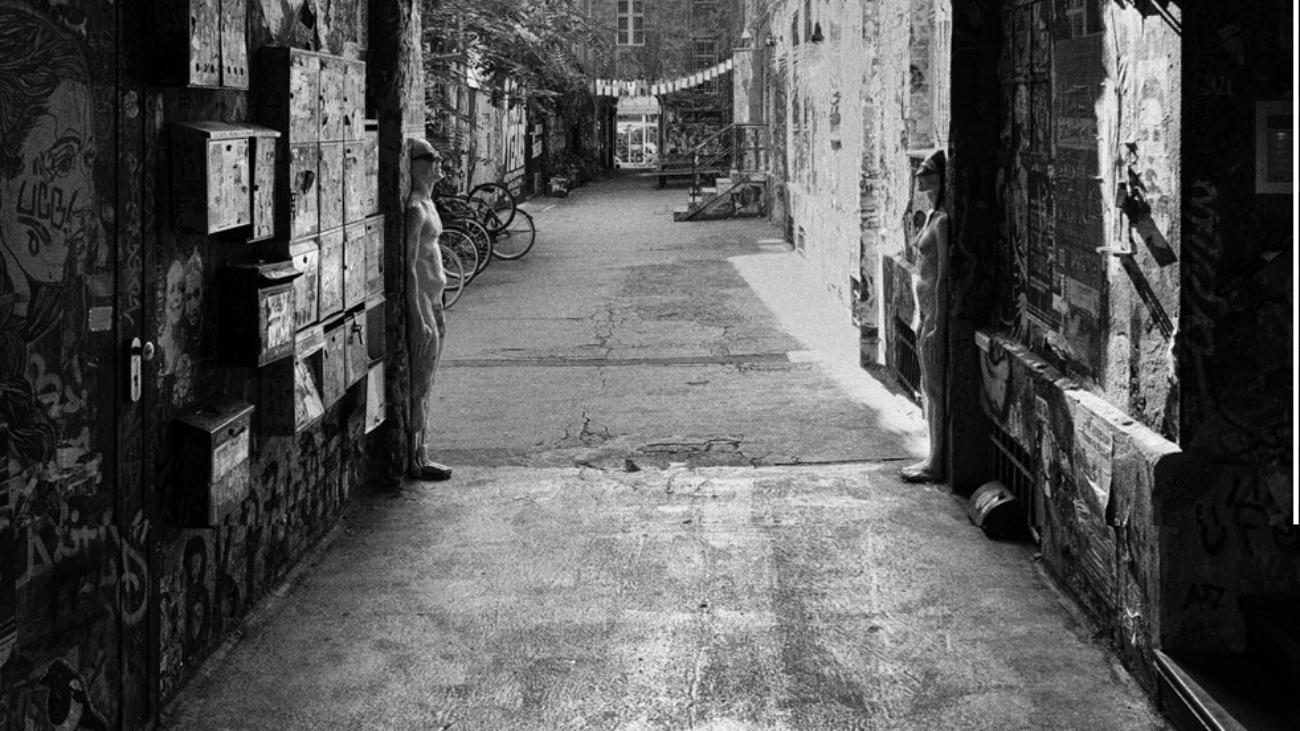

It makes me aware of how I spend my time. It helps me to accept it for what it is, or to stop it. I don’t think about the results. I’m just in the process. The whole point of being still is that I’m not thinking about the past or the future; it’s not about the past or the future. I’m the same person I was before I started this. Sometimes I even have the same stress. But I’m aware that there is also something else. So the important thing for me is this knowledge that comes with the stillness, knowledge about myself and the people and the life around me. At first, it was just me in this room standing still alone. But in the films after that, I’ve put myself in the society, in the middle of the city, and I am still there. It’s not a kind of religious awareness or the stillness of a monk who is alone and prays all day. It’s important for me to relate the stillness in my video to the movement of the society as a whole.

You want to show this contrast?

The contrast is important. To see these two things being there together at once. The stillness is what makes the activity clear. You wouldn’t notice the activity in the same way if there wasn’t this figure in the frame being totally still. There are all these timelines around me in the videos, being active, moving. And then there is the zero point. When you watch the video, it is as though there is something wrong, you feel like something is wrong because this one figure is not moving at all in the midst of all this other movement. It draws your attention to the stillness, and so you can’t help but notice this really typical street scene in a different way.

In being still for hours in the midst of a busy NYC scene, are you protesting all that movement? Or is this your way of saying “I accept this”?

I am accepting it. I don’t want to change it. I just want to see it as it is. I’m not resisting anything. I’m just stopping, just being there. It’s a place of timelessness. It’s the space in between the space. And I don’t know why I want to stay in this zero point, but I want to experience this.

It’s like by learning how to be with yourself alone, you found a way to really connect with the world again.

Once someone asked Tarkovsky what advice he would like to give the younger generation and he said the only thing he could say was that they should learn to be able to be alone with themselves, to learn how to feel the space and just be there with themselves. We are social animals and we cannot, nor should we, try to escape each other, but a society can’t do anything together if the people who create it aren’t comfortable enough to be alone with themselves first.

Interview by Andrea Hiott, New York City, 2009