NEVER EVEN

An interview with the filmmaker Jan Schomburg about his short film and how it is to be in a world where everything runs backwards.

Interview by Nicola Gerndt

Translated from the German by Anna Rohleder

Photo credit: Jan Schomburg

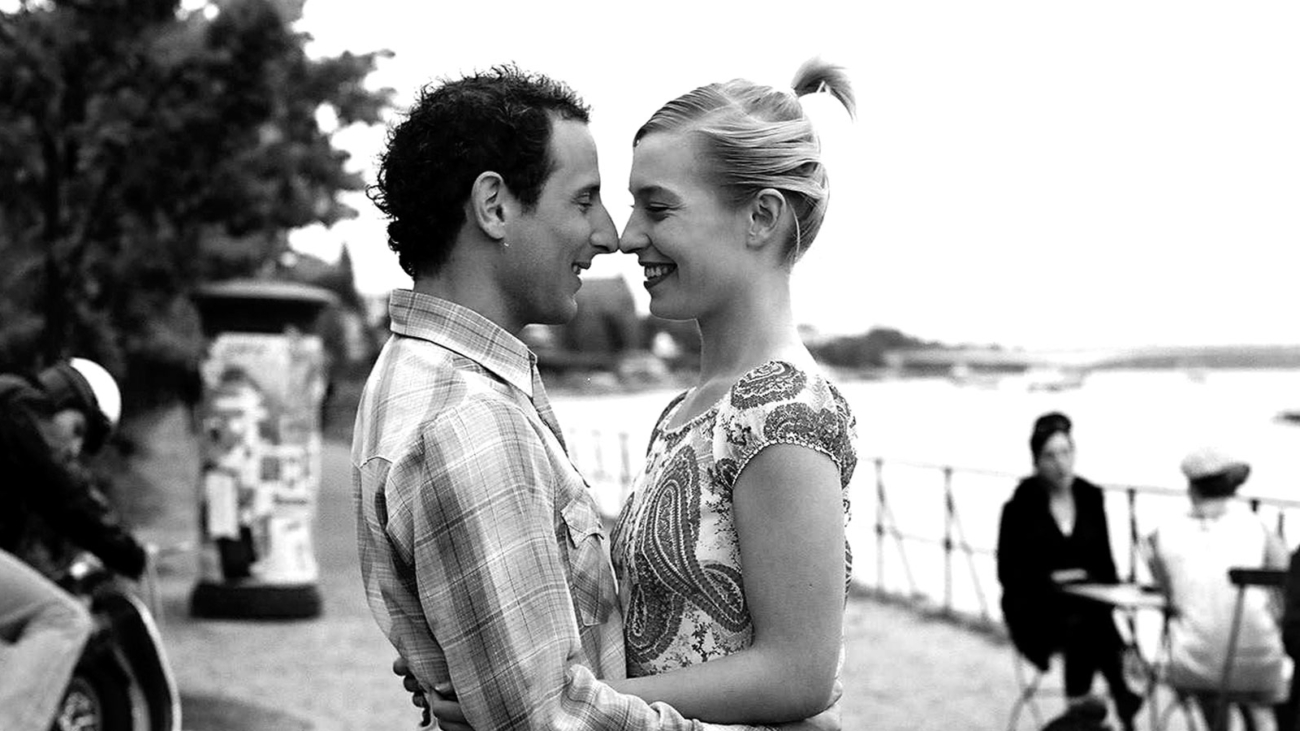

The second law of thermodynamics states that in any closed system, disorder or entropy increases over time. But what would happen if we suddenly found ourselves in a world where order steadily increased – where time ran in the opposite direction? In Jan Schomburg’s film “Never Even,” the main character Max wakes up one morning to find himself in a world where everything runs backwards. However, he is still living by his own chronology. He actually needs something to drink but that turns out to be a real problem: Water is being absorped by the tap instead of flowing into his cup and at the takeaway they give out empty bottles, where the people spit in liquid in order to give it back when it’s filled. Finally, the love of a young woman helps him to solve his problem by giving him what he needs to survive. She fills an empty cup with lemonade and gives it to him to drink, then stays with him.

Gerndt: How did the idea come about of letting the film run backwards?

Schomburg: Letting a film run backwards is probably the oldest trick in film history. It’s as old as the idea of making a person go forward in a world that goes backward. And once we started working with this subject we found out that there are some films that are structured on this same model. ”Never Even” is special because it takes the idea to its logical conclusion in an intellectual sense. We tried not to let the visual effect be the main focus in this film. We really wanted to do a thought experiment where certain demands were made on the viewer, where they were made to think a little bit.

Essentially there is also a certain preoccupation with time when you are making films because when you cut, you have these little pieces of time you edit together and partially see backwards. So it’s an obvious next step to make that idea the subject of a film.

… but it’s not only about the flow of time?

It’s about how someone can survive in a strange world, where everything runs in the opposite direction. The direction of motion is meant to be a metaphor for a mental or emotional direction – what happens when you find yourself in a world where nothing is familiar? How do you react to that, and how do you accommodate yourself to such a world.

Does it often happen that you feel like your main character – that you somehow feel you’re in the wrong place?

Actually I feel like that relatively seldom – generally I feel pretty comfortable in my own skin. But of course there are situations where I feel alienated and where I feel like what’s happening around me doesn’t have much to do with me. Funnily enough it happens a lot when I watch TV. I have a latent addiction to TV and keep my antenna cable in the basement so I don’t watch too much, but when I do get it out and start clicking through the channels it all seems very foreign because it is partially this parallel universe which is totally self-generated. I start seeing things that I don’t understand because they’re only related to other things on TV.

In “Never Even,” things return to their initial order. What’s negative becomes positive, crimes become nice gestures, someone who throws something away gets it back. Do you sometimes wish you could undo things that have happened?

Basically I find it interesting that – physically seen -the things in our world strive towards a higher disorder. If a glass breaks, its order is smaller than the one of an unbroken glass. In a world, where everything moves backwards, the things strive against it – purely physically seen – and into a higher order. Of course there are times when you think it would be nice if you could undo something. But in the end I’m more of the opinion that you grow from terrible things in the past, that they make you into the person you are today.

When the main character Max goes out looking for nourishment he meets a girl and falls in love with her. She gives him something to drink by putting a cup to her mouth, spitting out the lemonade and giving it to him. What does thirst mean here? Is it an equivalent of love, which humans also need to live?

Thirst is a very basic human need, and that’s also what it is in the film. But thirst isn’t an automatic equivalent of love. In the film it stands more for what makes us human, for the fact that we have certain needs which can only be met when we learn how to interact with other people, when we cooperate with them and help others. Even love in this context is a metaphor for interacting with others. Of course, thirst and quenching thirst, in that the woman fills a cup which the man then drinks from, has an erotic connotation too, but really in the end the point is just that we have certain needs and asks how they can be satisfied through our interactisn with others.

Without this lover who provides him with water, Max would be lost. It’s like the foreigner who would not be able to find his way in a strange place without the help of strangers. It’s communication without language, since words spoken backwards don’t make any sense to Max. The actions of the girl, like giving him water and her warm caring for him, help Max to survive, but at the same time they force him into a deep dependency…

I would see it differently in this case. What’s especially important from my viewpoint is that they fit together, that they find a way to unite the different directions they are going in, by dancing. I like that very much as a metaphor, because dance brings together two different directions. And at the same time dance is a great symbol for culture and art, because it doesn’t go backwards or forwards and welds both together. Ideally, it’s a form of communication when you do it properly. For me, this image

of dance in the film, even when it comes apart again, is a symbol for the way you can interact with someone playfully who is a stranger.

By giving him something to drink, she breaks through the passage of their different conceptions of time, as both are brought to the same level. If you let this scene run backwards, he would be giving her something to drink… What is love, is it symbiosis?

This scene is also paradoxical, because she does it twice, which actually isn’t even possible. That’s why it is like a symbiosis or a type of perpetual motion – suddenly something is generated from itself. She fills the cup and he drinks, then she fills the cup again. But that also means she can only fill the cup because he drank from it. And if you stay with these different directions, it becomes apparent that drinking for him is excretion for her. In that sense, of course it’s symbiosis. And that’s where the suspension of thinking in terms of direction begins.

Why does she stay with him? If you kept the story going, he would just get older and more unsightly…

As for becoming unsightly, it raises the question of what the ideal of beauty really is in a world where everything runs backwards. In our world it is like that – the older you get the more unsightly you become, and in the backwards world it’s perhaps exactly the same that the old persons are juvenile there and the young people old. But we’re dealing with a love here which is above the concerns of age.

But they are really about the same age when they meet. That’s when things get started for both of them with each other.

Right, and the melancholy at the end constitutes, because in the finish they are really united in death. He will die like we do and she will break down into a sperm cell and an egg. That’s when they will really become one.

In the last scene we see him as an old man holding an infant in his arms, which is supposed to be her. For us it’s kind of the image of a grandfather…

Absolutely. It’s also referring to the fact that when you get old you become a bit infantile again and maybe it’s all at the same level. When I was about 12 I had fantastic conversations with my great-aunt about Hermann Hesse, which you can enjoy reading apparently only under or over a certain age. I think when you get old you become a little simpler in your feelings, more immediate, you’re not thinking anymore about a career and you have time again for the things you liked doing when you were a kid. That’s why I can imagine that in the film those two characters really understood each other when she’s 6 and he’s 60…

Why did you choose the title “Nie solo sein” (Never alone)?

“Never Even” is the title of the film in English, which actually means something quite different. You’re somewhat limited by language when you want to create a palindrome, in other words, if the title is supposed to read the same forwards as well as backwards. And since “never alone” isn’t a palindrome in English, we looked for something else, and “never even” was a title that also fit the film.

How was the film received abroad?

It was received very well everywhere – the humor of it is universal. Everyone can follow it because everyone’s thought of something like it at some time. In the end it’s a very intuitive thought experiment.

The film was awarded various prizes – did you expect it to be such a success?

To be honest, we did actually expect that. The other films I’ve made are rather depressing tragedies that are a bit hard to digest, and I thought, I should try to make a movie that is fun for the audience. At the same time it’s also a film that fits in with the festival formula because it’s a very intuitive idea that’s immediately comprehensible. Though at the beginning we got a lot of rejections. The film had a relatively slow start, then gradually things improved. The high point was when it was shown

on the closing night of the New York Film Festival before 2,800 people in Avery Fisher Hall as the supporting movie for “Sideways” by Alexander Payne.

How did the film change you – you said you started dreaming backwards at that time?

It was a bit strange to spend all day thinking about how things go backwards – is it logical for him to do that, shouldn’t he smile earlier… At some point those thoughts just get in your head so that at night you also start dreaming backwards. Fortunately that more or less subsided and I won’t make another film backwards again anytime soon.

What’s next for you?

My next project is to make a science fiction film in collaboration with the ZDF channel’s “The Little TV Play”. Shooting will start in spring 2006. It’s sort of similar in a way to “Never Even” as it’s also a relatively clear external idea, although my hope is that I can combine the tragic and depressing for the first time with a light, charming topic in this film, as was the case in “Never Even.” The story in this movie is that in the year 2020, plastic surgery has been perfected to the point that a 70 year-old can be surgically transformed into a 20 year-old without anyone being able to notice. In that sense the “old/young” subject is there again, but this time with the question of what really is this bodily shell if it can be modified arbitrarily, what does that mean for our identity. A philosophical, theoretical inquiry which is hopefully going to be a lot of fun.